By Brooke Schwartz, LMSW

In a previous blog, we discussed emotion dysregulation, which is the inability to regularly use healthy strategies to diffuse or moderate negative emotions. It’s common for parents to wonder whether their child is engaging in typical, normative, or age-appropriate behaviors, or whether they are experiencing more persistent emotion dysregulation. This may bring about even more questions about what kind of treatment might be effective for their child.

For those who suspect their child struggles with emotion regulation, it’s worth keeping in mind that emotion dysregulation is not a disorder. Rather, it is an umbrella term for a variety of behaviors that may occur in isolation or in combination with each other. These behaviors — such as frequent irritability or regular and severe temper tantrums or outbursts — are often listed as the criteria for various disorders. Which ones? Research shows that emotion dysregulation may be associated with the following:

For those who suspect their child struggles with emotion regulation, it’s worth keeping in mind that emotion dysregulation is not a disorder. Rather, it is an umbrella term for a variety of behaviors that may occur in isolation or in combination with each other. These behaviors — such as frequent irritability or regular and severe temper tantrums or outbursts — are often listed as the criteria for various disorders. Which ones? Research shows that emotion dysregulation may be associated with the following:

-

Neurodevelopmental disorders. Children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) may exhibit behaviors related to the dysregulation of both negative and positive emotions. That is, children with ADHD may not only experience difficulty managing anger and frustration, but also emotions such as excitement or exuberance. Both, ultimately, may impede their ability to respond to their environment with flexibility or in a socially adaptive manner. Relatedly, because emotion regulation is a strong predictor of academic performance, it’s possible that emotionally dysregulated children experience other academic difficulties or even receive specific learning disorder diagnoses.

-

Anxiety disorders. Research shows that children with anxiety struggle more than their non-anxious counterparts both to decrease negative emotions and to employ effective emotion regulation strategies. One study found that while anxious children may be able to regulate and achieve substantial emotional relief in specific conditions, these methods may not be applied often enough in every day life.

-

Disruptive, impulse-control, and conduct disorders. Children who are emotionally dysregulated may engage in aggressive or impulsive behaviors, which may be in line with diagnoses such as oppositional defiant disorder, intermittent explosive disorder, or conduct disorder. In fact, one study concluded that oppositional defiant disorder is better conceptualized as a disorder of emotion regulation, rather than as a behavior disorder.

-

Mood disorders. Emotion dysregulation may be considered an etiological factor behind the frequent, severe temper outbursts and irritability of a newer diagnosis called disruptive mood dysregulation disorder.

Because behaviors captured under the emotion dysregulation umbrella are associated with a variety of disorders, it’s possible and not uncommon for parents to mis-conceptualize their child’s behavior. For example, a parent may hear from their child’s teacher that the child is having difficulty tolerating anger and frustration in the classroom. A parent may suspect that their child is experiencing a mood disorder — and even seek out related treatment — when their child is perhaps experiencing symptoms of ADHD.

What’s a parent to do if they suspect their child is emotionally dysregulated? There are a variety of ways you may choose to respond effectively to your child’s emotion dysregulation, such as by:

-

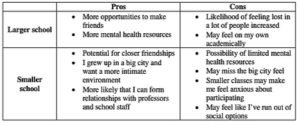

Modeling emotion regulation. Talk about the emotions you experience and what coping strategies you’ll use so that your child sees emotions being regulated. This may mean using positive self-talk or creating a pro and con list in front of your child when your own emotions escalate.

-

Validating. Validating means communicating to someone that what they are feeling, thinking, or doing makes sense (it does not mean you agree with it). With emotionally dysregulated children, validate the thought or emotion rather than the behavior. For example, if your child is kicking, crying, and screaming, you may validate by saying, “I can hear how angry you are,” or “It makes sense that you’re upset that I turned the TV off.”

-

Praising efforts to regulate emotions. Not only does praise feel good, it also lets your child know what you want to see them doing more of.

Praising efforts to regulate emotions. Not only does praise feel good, it also lets your child know what you want to see them doing more of. -

Role-playing. Practice emotion regulation when your child is already emotionally regulated. If you know that your child becomes emotionally dysregulated at bedtime, practice going through the bedtime routine earlier in the day, having your child practice following specific instructions (for example, “speak in a soft voice,” and “walk from the bathroom to your bedroom”). Praise them as you go.

-

Considering treatment. A variety of modalities are shown to be effective in treating emotion dysregulation among children, such as Dialectical Behavior Therapy, Mindfulness Meditation, and Parent Management Training. Parents often play a role in their child’s treatment, however the emphasis on parent involvement varies depending on the modality.

Whether or not you’re engaging in treatment — and even if your child isn’t emotionally dysregulated — the tips described above can help increase your child’s potential to effectively regulate their emotions.

Disclaimer

This site is for information only. It is not therapy. This blog is only for informational and educational purposes and should not be considered therapy or any form of treatment. We are not able to respond to specific questions or comments about personal situations, appropriate diagnosis or treatment, or otherwise, provide any clinical opinions. If you think you need immediate assistance, call your local emergency number.

For referral information about our services, please click here or see our contact page on our website.