Invalidation is one of the most corrosive factors in any given relationship. After all, chronic invalidation resides at the heart of DBT’s Biosocial Theory, which expounds upon why one may struggle to control one’s own emotions and actions. Invalidation, at its core, “tells you your emotions are invalid, weird, wrong, or bad” (Linehan, 2015). It can take many different forms, and while the intention may not be harmful, the impact very well might be. Whether at home, at work, in school, or at a social gathering with friends, it is possible that invalidation will arise.

Invalidation is one of the most corrosive factors in any given relationship. After all, chronic invalidation resides at the heart of DBT’s Biosocial Theory, which expounds upon why one may struggle to control one’s own emotions and actions. Invalidation, at its core, “tells you your emotions are invalid, weird, wrong, or bad” (Linehan, 2015). It can take many different forms, and while the intention may not be harmful, the impact very well might be. Whether at home, at work, in school, or at a social gathering with friends, it is possible that invalidation will arise.

Some examples of invalidation might look like being ignored, receiving unequal treatment, or being told any iteration of the following:

- “Stop being such a drama queen!”

- “You have to move on from this. Normal people don’t care this much about _____.”

- “It’s not that bad.”

- “You’re seriously overreacting.”

- “Just get back on the horse.”

People in your life who invalidate you are typically doing the best they can in the given moment. Perhaps they aren’t sure what or how to validate you, or they’re experiencing distress watching your distress, and are seeking to ameliorate it as quickly as possible. For example, I distinctly recall driving to prom with my very well-intentioned mother when I was 18 years old. I was feeling insecure and uncomfortable in my own body, and when I shared this, my mother said: ‘You look great! Don’t worry about it!’ My distress was so discomforting to her that, rather than validating my emotions, she proffered a different form of invalidating feedback. This makes sense, in so many ways. Who wants to witness their own child in pain? And, this wasn’t what I needed in that moment, and only furthered my sense of distress.

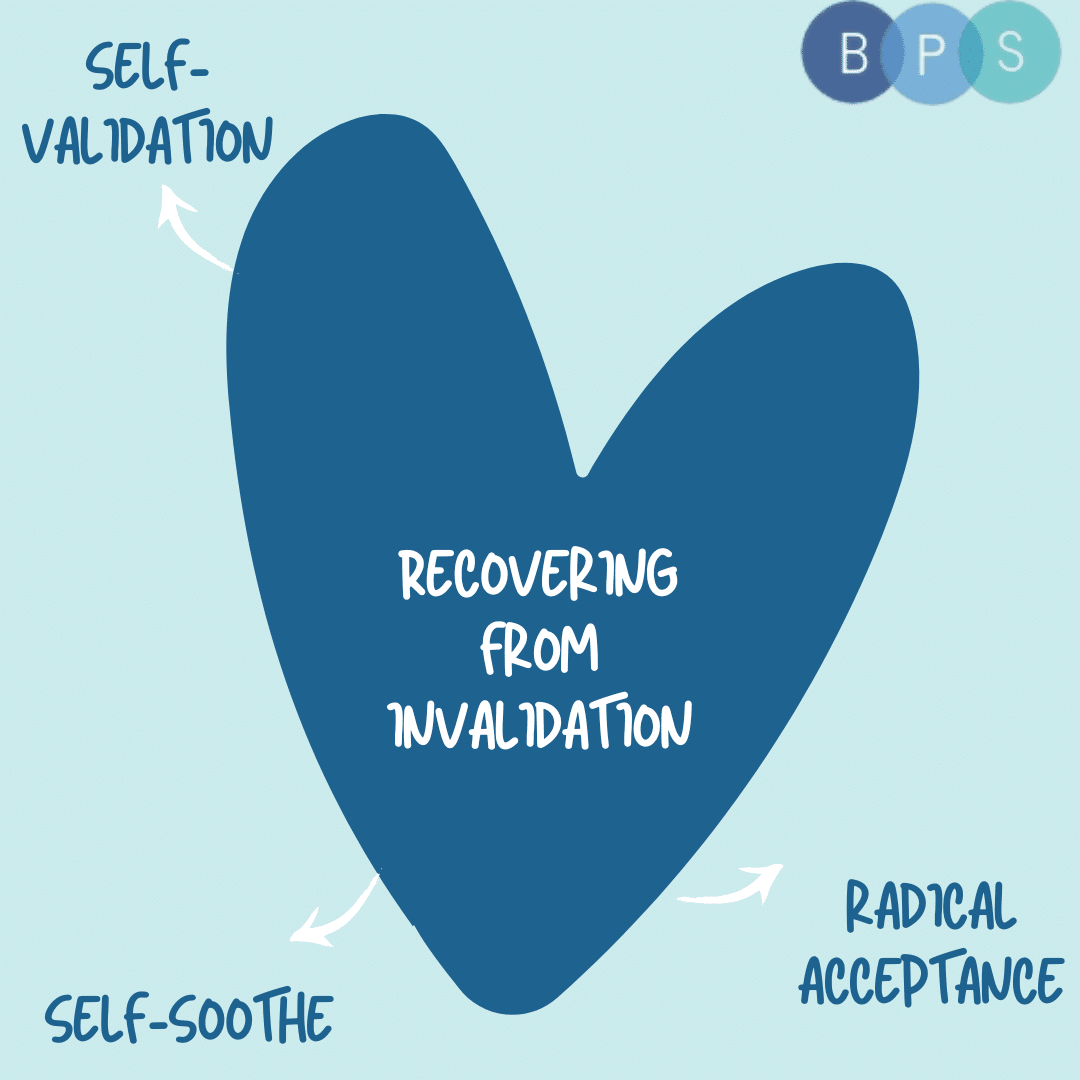

Oftentimes, people who invalidate others grew up in invalidating households or social environments. This behavior was learned, over time, and it’s not uncommon that the individuals invalidating you may also be persistently invalidating themselves. This consideration can be a useful tool for building compassion in the face of invalidation, and for removing the inclination to judge and blame — which only contributes to further suffering. Whatever the cause, we have collated three of our favorite skills for responding to an invalidating environment.

Skill 1: Self-Soothe

While it may be difficult to self-soothe in the presence of the individual who has invalidated you, take some time in the wake of the invalidation to practice self-soothe. You are feeling pain, and that make sense! Practice self-soothing with the six senses (sight, touch, smell, taste, sound, and movement) to re-regulate, and move forward effectively. Sometimes this requires planning ahead with some self-soothe objects or materials. As a starting point, take a look at these ideas for each sense:

- Sight: Watch a funny YouTube clip from your favorite television show. Go outside and catch the sunset. Pull up a picture of a time that made you feel safe and content.

- Touch: Purchase some silly putty or a fidget spinner. Pet your cat or dog. Take a nice, long bath or shower.

- Smell: Brew some fresh coffee or light a candle that you love. Put some hand lotion on and notice the smell.

- Taste: Mindfully eat a favorite food or drink a healthful beverage that you enjoy.

- Sound: Listen to your favorite playlist, or pull up a recording of a stream, rainstorm, or bird calls.

- Movement: Go for a walk outside or try a minute of jumping jacks or burpees. Dance in your bedroom!

Skill 2: Self-Validate

While we may be skilled at validating others, it’s often the case that we forget to or struggle to validate ourselves. Use the Six Levels of Validation on yourself, just as you would with a loved one.

Skill 3: Radical Acceptance

Radical Acceptance is a key component on the path towards minimizing suffering. While pain is a fact of life, suffering is a choice. Acknowledge and validate the pain of the invalidation you’ve experienced, and then practice exercises like turning the mind, willing hands, or half-smiling to bolster your pursuit of relief from pain. It may be useful to imagine the invalidating person in your mind’s eye while practicing willing hands or a half-smile, for example.

Remember, some skills work for some people some of the time, so practice makes progress with all of the above!