Recently, in an off-handed, quasi-self deprecating way, a dear friend remarked to me, “If I were to speak to others the way I speak to myself, I don’t think I’d have that many friends.” I was struck by the statement, as my assumptions about this individual ran wholly counter to her internal experience.

“What do you mean?” I asked. (As we know in Dialectical Behavior Therapy, it’s ever-important to check the facts, lest our interpretations and assumptions run wild.)

“Oh, I just…I’m pretty cruel to myself. Just a lot of me judging me for being me.” She continued with specifics, and I was dumbfounded. All this time, my dear friend, the ‘Queen of Pep Talks’ as we call her, was evaluating herself — and not positively. At the very least, not in a fact-based light.

And you know what happened? Essentially right after I registered that I was experiencing surprise? I had a rapid fire series of thoughts, noticing this one in particular: ‘Even with my training and experiences in social work, I totally assumed that she was inured to this type of evaluation and labeling. Wow.’ I judged myself.

Well, well, well.

Upon further reflection, as well as additional use of my Mindfulness WHAT and HOW Skills, I came to a conclusion that I hadn’t yet named for myself: Perhaps I am also my harshest critic. Perhaps many of us are. (And yes, I’m going to be transparent in naming that I subsequently judged myself for coming to this conclusion, as I had the thought: ‘Duh, Avery.’)

Knowing how much we lose by judging our perceived flaws or missteps, how much pain this can bring about, and how both of these things can prompt maladaptive behavioral responses, what’s to be done? How do we tackle the seemingly automatic judgments and self-criticisms that many of us have towards ourselves? A potential answer resides in the work of Dr. Kristin Neff, a pioneer in the field of self-compassion.

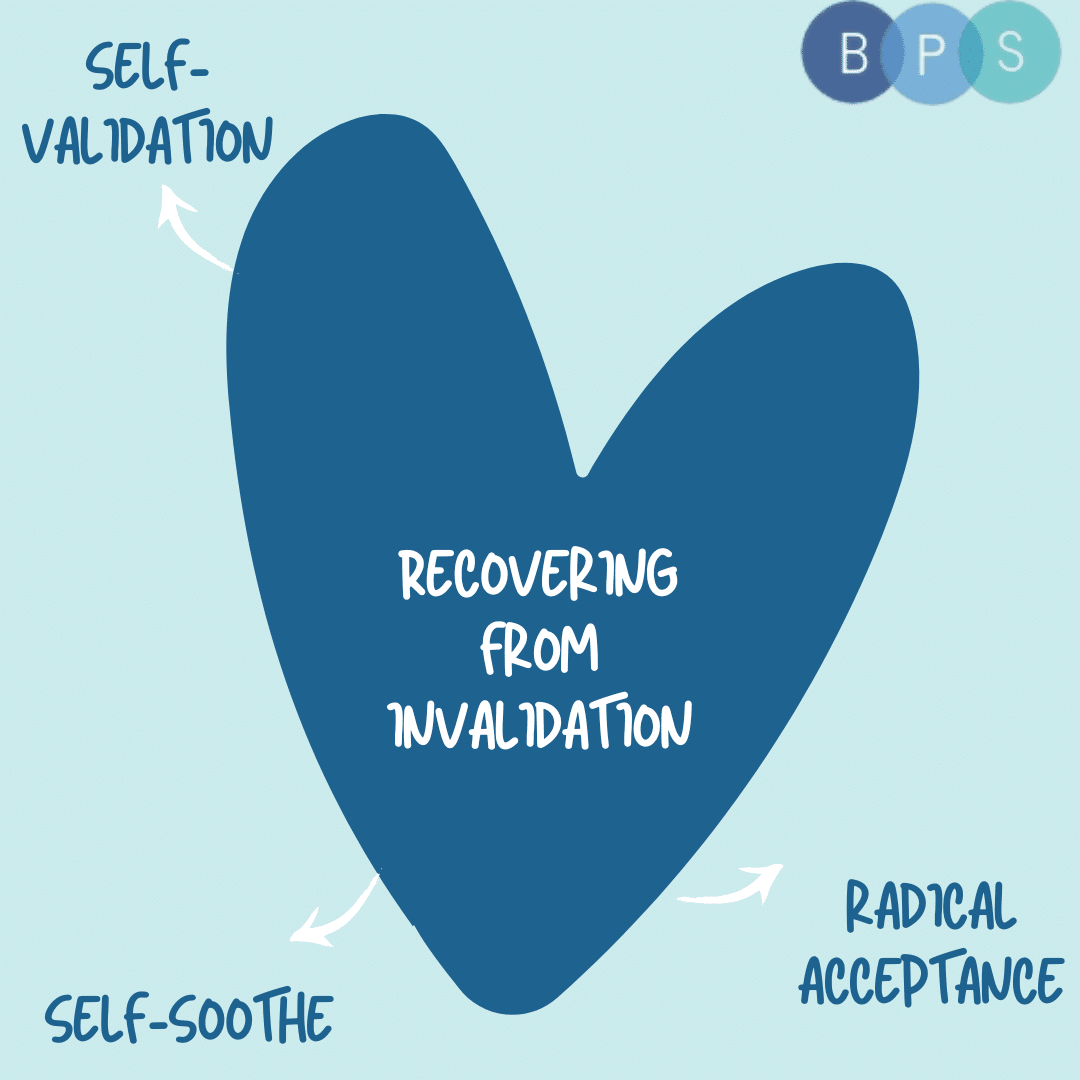

Self-compassion is a Buddhist psychological construct that acts as a healing balm, a salve, in the face of self-criticism and judgment. It is something that can be practiced, flexed like a muscle, and it is best summed up — funnily enough — by treating yourself like you might treat a loved one. It is made up of three components:

-

Mindfulness or bringing a balanced awareness to the present moment (consider your mindfulness skills!)

-

Self-kindness or offering ourselves warm, gentle acceptance and comfort (consider your self-validation skills!)

-

Common humanity or recognizing that pain and challenges are part of the shared human experience (consider radical acceptance!)

A blogpost is not sufficient to encapsulate all the tenets of what self-compassion is, what it is not, and how to practice it. AND, to begin seeding that habit of self-compassion, a new behavior to learn and nurture, I am sharing two self-compassion exercises to get you started. These are inspired by, although slightly modified from, Dr. Neff’s work.

Exercise 1: Loving Kindness Meditation

In a space that feels safe and comfortable for you, position yourself in a mindful, wide awake position. Remember: No past. No future. Just the present moment. Let your mind run away. Catch it — and return.

Take several deep breaths in, and repeat the following phrases, or modifications that you prefer, to yourself:

May I be happy

May I be healthy

May I be at ease

May I give and receive warmth

Notice any thoughts, emotions, physical sensations, judgments that come up for you. Stay with this, or direct your loving kindness to others.

Exercise 2: Supportive Touch

Offering yourself a form of supportive touch is shown to release oxytocin, enhancing security and calming distress. Try any of the below motions, after taking several deep breaths, and notice what comes up for you:

One hand on your cheek

Cradling your face in your hands

Gently stroking your arms

Crossing your arms and giving a gentle squeeze

Gently rubbing your chest, or using circular movements

Hand on your abdomen

One hand on your abdomen and one over heart

Cupping one hand in the other in your lap

As a note, there is a clear and marked overlap between the foundational components of DBT and self-compassion. This infusion may be fruitful, and I highly recommend exploring Dr. Neff’s website, here, alongside the following texts:

For Children

Listening with My Heart (Gabi Garcia)It’s Ok: Being Kind to Yourself When Things Feel Hard (Wendy O’Leary)

For Teens

The Self-Compassion Workbook for Teens (Karen Bluth)

For Adults

Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself (Kristin Neff)

Radical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life with the Heart of Buddha (Tara Brach)